Tag Archives: Dr Oliver Robinson

In for the long run: how a longer life caused your quarter-life crisis

Call us pedantic, but here at Clueless we’re a bunch of perfectionists. We like our beers cold and our Ginsters hot, our water parks big and our crazy-golf scores small. We also like to know why things are going wrong, and how we can stop them – which is why we got in touch with The Office for National Statistics (ONS) and quarter-life crisis expert Dr Oliver Robinson to see how modern day adulthood affects the QLC.

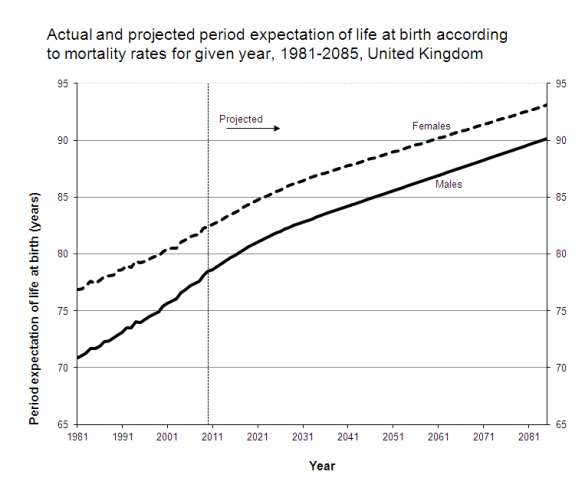

It turns out it all starts with life expectancy. Yep, living longer is actually a massive downer. The ONS gave us these stats:

For full statistics, click here

As you can see, life has gotten a lot longer over the past 100 years. But how is that related to the QLC? Well, it all starts with the age adulthood begins. According to Dr Robinson, for most of the 20th century 21 was deemed the age adulthood started (so three extra years of sponging off your parents – nice). When combined with the average life expectancy of the period in question, it meant you started working and living independently later, and, as you were expected to die a lot earlier, you were working for a much shorter period of time (yay!).

Instead now we start adulthood at 18 (and some of us start our careers as early as 16, for example in apprenticeships) and work until around the age of 70 – that’s a lot more early mornings, traffic jams, and mind-numbing toil. Now consider the fact that most 18 year-olds don’t actually consider themselves adult until six or seven years later and you see the problem; being thrust into an uncomfortable position of independence at 18, a position which you don’t feel you’re ready for, and you’re likely to get stressed out – but looking ahead and seeing decades and decades of the same is just plain depressing.

And unfortunately, it isn’t going to get any better. With life expectancy in the UK rocketing, the forecast for future generations looks even bleaker – better keep a spare room in your future house, because there’s a fair chance that the kids will be moving back in…

If you fancy hearing more academic insights into your QLC then check out Dr Robinson’s Clueless guest post!

If you fancy hearing more academic insights into your QLC then check out Dr Robinson’s Clueless guest post!

Guest post: Dr Oliver Robinson

The Clueless team has only gone and snagged Dr Oliver Robinson for a bit of academic, incisive QLC discussion – lucky us! Doc Robinson is Programme Leader for the BSc Hons Psychology with Counselling degree at the University of Greenwich. He’s something of a QLC expert, and his research has been published in the New Scientist, The Guardian, BBC Radio 4, The Telegraph and The Times (Wow. We actually are lucky). Today he’s going to wax lyrical on the basics – what is a QLC, and where does it come from? This is the kind of guy who has many leather bound books and a Rolodex, so listen up people…

What is the quarter-life crisis? After all, traditionally the period of midlife has been most strongly associated with having a crisis in adulthood, but it is now widely accepted that they are just as likely in the first decade of adult life. A quarter-life crisis is a period of stress, instability and major life change that occurs when a person is either in their twenties or early thirties. Such a period typically occurs when a person has entered a job, relationship or marriage, or has developed an adult lifestyle, which they then realise they no longer want because it is causing them distress or preventing their personal growth. The crisis period acts as a turning point during which old commitments are ended, new ones are begun, and many strong emotions are experienced. Crisis episodes are often reflected on as developmental important periods, during which much personality development and emotional development occurs.

“A quarter-life crisis is a period of stress, instability and major life change that occurs when a person is either in their twenties or early thirties”

My research has investigated the quarter-life crisis using questionnaires and interviews, and I’ve found it is quite a common phenomenon – about one third of British adults aged 30 and over reflect on having a crisis in their twenties.

However, there are good arguments that the quarter-life crisis is more common now than in the past.

Firstly, adults in their twenties report higher levels of stress than any other adult age group. It is a time during which major decisions are made that shape the remaining decades of adult life – this is a source of pressure and anxiety and one that is increasingly complicated in the modern world as there are more kinds of job, more possible identities and a wider set of options for relationships.

Courtesy of Alex Anderson, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

An additional challenge for young adults is changing roles from being a dependent child who lives at home and is financially supported, to being an independent adult. This transition to adulthood can take many years to achieve in full due to longer periods studying and the high price of property.

While age 18 is the commencement of legal adulthood in the UK (and many other countries), most young adults do not actually think of themselves as adults for some years after that. This is referred to as the stage of ‘emerging adulthood’ – when a young adult is neither fully adolescent nor fully adult.

In the past, the start of adult commitments such as marriage, parenthood and career occurred earlier, so by the age of 25 a young person would quickly be embedded in adult society through entering these social roles. Now, in the UK, the average age for first marriage is approximately 30, and parenthood also starts at this age on average.

This delay of commitments means that a young person has more freedom to explore and be educated than ever before; it means that major life changes are more possible and manageable. For example, a career change is easier if the person does not have financial responsibilities towards children and so has the capacity to re-train for a period of their young adult life, while a relationship change is also easier if the relationship in non-marital and does not involve children. These are the kinds of changes that make quarter-life crisis a more common phenomenon than in the past.

A quarter-life crisis is an episode in life that typically lasts a year or two, and includes a number of recognisable features. All episodes start with Phase 1. This involves a life situation that is causing the person stress, dissatisfaction, a deep sense that their development is not progressing healthily and optimally, and feeling trapped in a set of commitments that have been made but are no longer wanted. This is often accompanied by not feeling in control– of being pushed around by circumstance and other people. The negative emotions that characterise Phase 1 are often held within, and not expressed outwardly.

Phase 2A brings with it a greater desire for change, and a belief that change can occur. During this phase, a person separates from a relationship, social group or job to search for a new path into adult life. This is a distressing period, for it brings a sense of loss, confusion and a sense of anxiety about the future.

“Rather than living with a routine and automatically, life in Phase 3 is experimental and spontaneous”

Phase 2B is a time of questioning and self-examination. One of our participants said of this period: ‘‘I had to reflect, I had to see about the past and what went wrong, why things went wrong”. This emphasises the nature of this period – a time to reflect on why their life had led to a crisis and how to move forward.

Rather than living with a routine and automatically, life in Phase 3 is experimental and spontaneous. New ideas, identities and commitments are then tried and a person looks at options available to them for the future. The aim of Phase 3 is to search for a career or relationship that is more closely aligned with their ‘core self’ – they values, aspirations and deep sense ‘who I am’ than before.

Phase 4 is termed the ‘rebuilding phase’ and it involves active steps towards building a new adult ‘life structure’ – an integrated set of commitments that can stand the test of time and act as the foundation for the decades of adult life to come.

To read more of Doc Robinson’s work on the QLC and coping with adulthood, check out his book Development through Adulthood: An Integrative Sourcebook. You can also catch excerpts of his keynote speech at Mind The Gap’s launch party in March on our liveblog coverage of the event.